So many seminal innovations in modern art were greeted by varying degrees of disdain, outrage, and mockery. Rothko, Pollack, Warhol, Kandinsky, Koons—who hasn’t heard a gallery-goer exclaim, “Sheesh! Even I could do that.” (What’s the only true reply? “Ah, maybe…but it’s too late.”) When James Thurber’s cartoons appeared in the New Yorker magazine, “mothers…sent in their own children’s drawings…and I was told to write [them and I wrote] the same letter: ‘Your son can certainly draw as well as I can. The only trouble is he hasn’t been through as much.’”

Indeed, Thurber’s unschooled, quickly executed art unsettled readers and critics alike. All were at pains to explain why on earth they were so funny—or, even more challenging: what they were. “A Thurber must be seen to be believed—there is no use trying to tell the plot of it. Only one thing is more hopeless than attempting to describe a Thurber drawing, and that is trying not to tell about it.”—Dorothy Parker

Other reviewers hazarded these words, claiming Thurber’s cartoons… “[are]…ectoplasmic figures, seemingly executed in a telephone booth between wrong numbers…,” “…something scribbled on the back of a napkin…like an office gag shared at the water cooler…,” “…may have been influenced by what he has seen in Egyptian tombs…,” “…have the outer semblance of unbaked cookies.”

Thurber himself took pride in underscoring that he was, in no way, a “fine artist.” “Some years ago my eye doctor told me, it’s a miracle I didn’t go completely blind when I was seven years old, and he added, thoughtfully, ‘It’s hard to believe God really wanted you to do these drawings.’”

Veteran New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff offers this, regarding Thurber’s work…and that of others’ for whom his minimal style flung wide the door: “It’s the think, not the ink.”

"It's a naïve, domestic burgundy without any breeding, but I think you'll be amused by its presumption."

Originally published in the New Yorker, March, 27 1937.

American male tied up in typewriter ribbon, originally appeared in Let Your Mind Alone (1937).

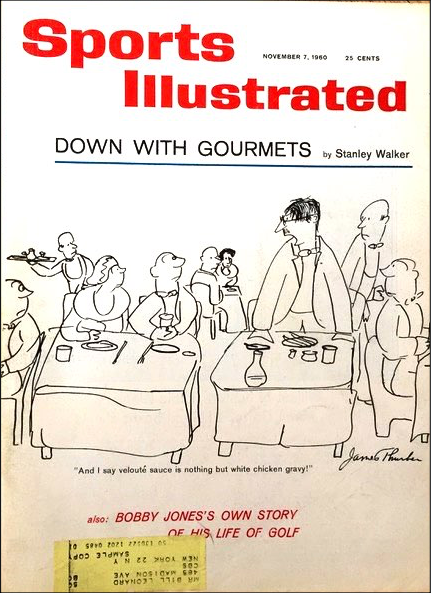

Sports Illustrated cover, 1960

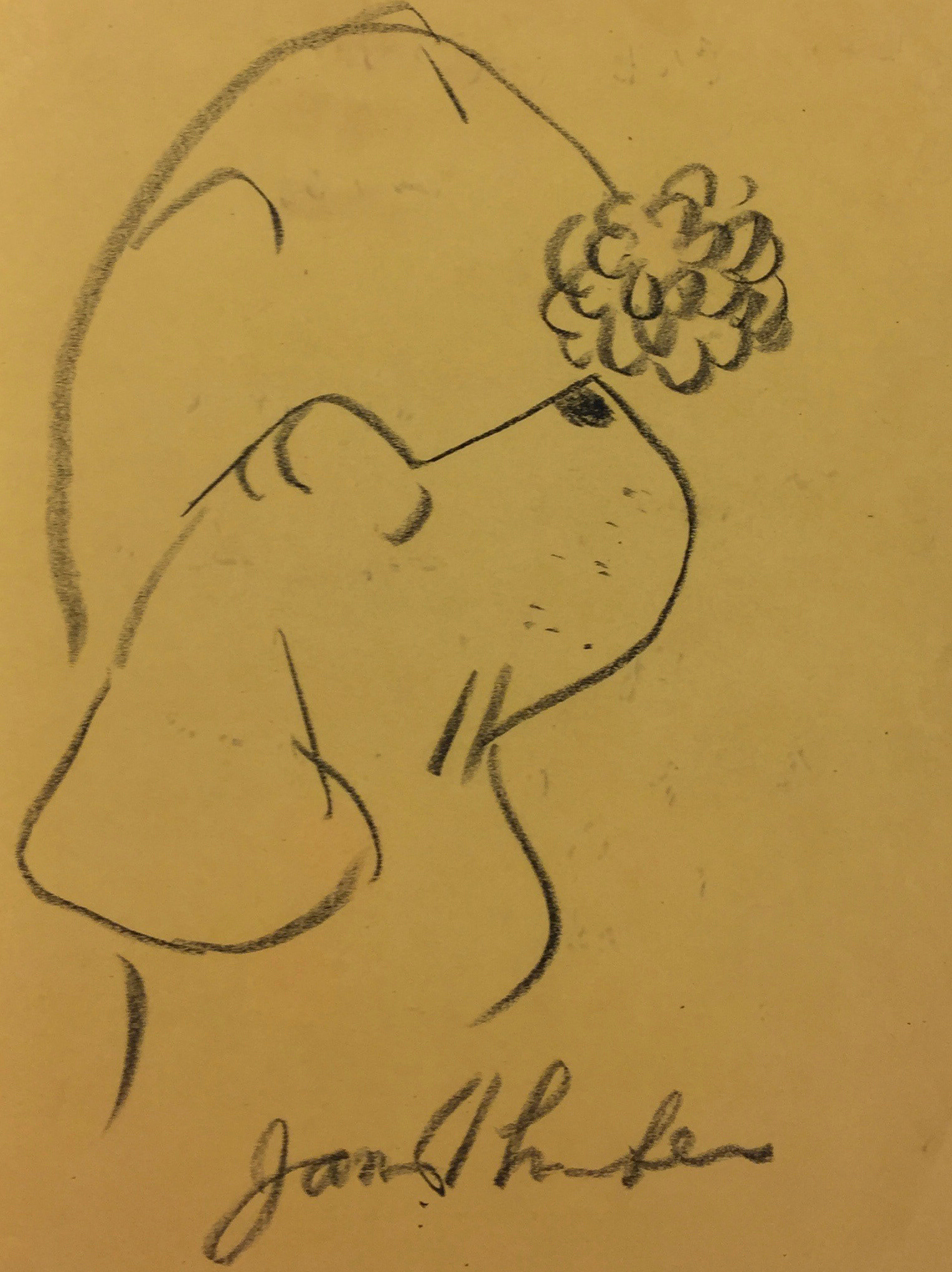

Dog and flower yellow page

One of several covers Thurber submitted to the publisher for My Life and Hard Times. Previously unpublished it now appears in the Columbus Museum of Art exhibit and in the accompanying monograph, A Mile and a Half of Lines.

In 1926, when Thurber entered the year-old New Yorker magazine as managing editor, its cartoons presented regimented, typical situations; it’s skillful artists created handsome drawings accompanied by short narratives or bits of dialogue. (The US Bureau of Cartoons was still sending weekly bulletins to cartoonists nationwide, suggesting subjects by various government agencies: popularize the draft, save food and fuel, sell Liberty Bonds.) But like the writing, New Yorker drawings looked to cast aside the pedestrian and appear more sophisticated.

With E. B. White’s encouragement—indeed, White first inked in Thurber’s cast-off pencil drawings and repeatedly presented them to the magazine’s not-quite-convinced art committee—Thurber, the untrained artist of few unstudied lines, began publishing humorous drawings with single-line captions.

In 1938, cartoon historian William Murrell wrote, “The sources of Thurber’s inspiration are impenetrable; his indefinite people ooze mystery even after they are drawn. They are children of the subconscious, and if the hand that draws them becomes more skilled they will vanish beyond recall. And it is more than likely that Thurber knows this too.”

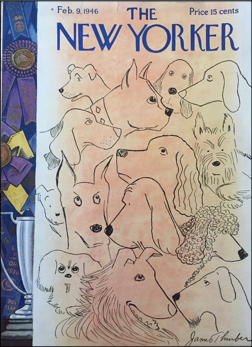

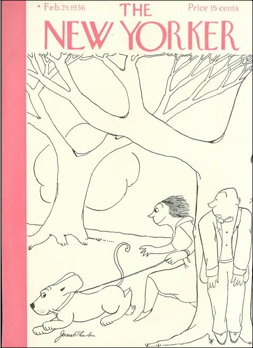

New Yorker, Westminster Dog Show cover,

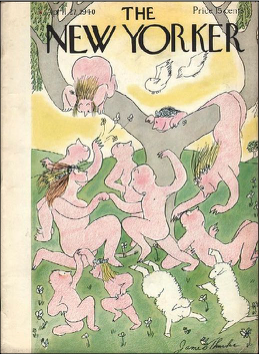

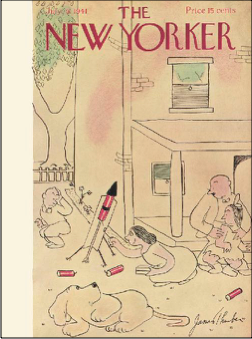

New Yorker baccanalia cover, 1949

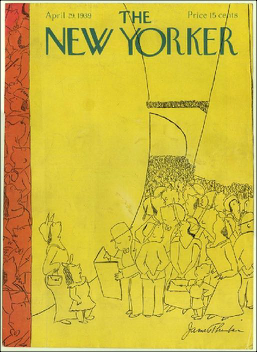

New Yorker, World's Fair cover

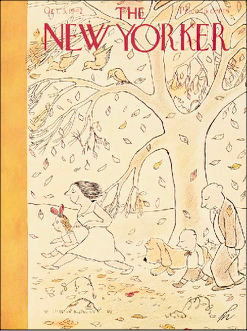

New Yorker cover date

New Yorker cover

New Yorker, February

All illustrations by James Thurber are copyright protected and may not be downloaded, reproduced, or otherwise used without the express permission of the Barbara Hogenson Agency. Please find information in the Contact section of this site.